24

In dulci jubilo

It’s hard to imagine Christmas without music, and it’s hard to imagine Christmas without singing, whether you still know the words, listen to a Christmas oratorio or prefer to let Spotify help you out. The roots of our Christmas carols lie in the Middle Ages, when German-language melodies began to prevail alongside Gregorian hymns sung in Latin. These, the so called “Leises”, could also be sung along by ordinary parishioners who did not know the old language. The songs usually ended in a Kyrie eleison, the Greek “Lord, have mercy” of the liturgy, and thus got their name.

Probably the oldest hymn known to us, “Praise be to you, Jesus Christ” from the 14th century, was later adapted by Martin Luther. Luther was, as is widely unknown, a great lyricist and composer of church hymns, which are still so catchy and beautiful today, they are not only in the Protestant, but also in the Catholic hymnal.

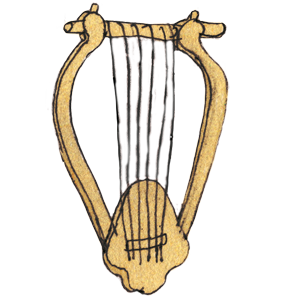

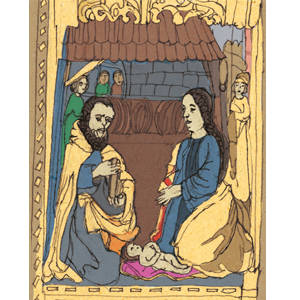

The artist of the Gothic Marian altar in the Cathedral of St. Sebastian, on whose central section the Nativity scene depicted here can be found along with three other images from the life of Mary the Mother of God, was not particularly interested in angels playing music or shepherds singing carols. What is remarkable, however, is his Annunciation scene, quite unusual in terms of iconography and music, where the Archangel Gabriel does not hand Mary a lily as usual and gently prepare her for the conception of our Saviour, but rather blows into a golden horn, presumably a Jewish shofar, which undoubtedly points very loudly to the arrival of the Messiah.

Merry Christmas !