24

“Mary, Spread out Your Cloak”

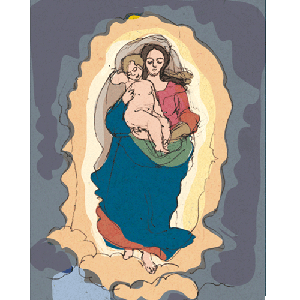

The cloak is blue and wide. It not only envelops her figure and protects the child, but has also been a refuge for the whole community since the early Middle Ages, when Christians began to confide in the Mother of God in their worries and needs. Blue not only stands for purity, truth and faithfulness, but is also a symbol of Mary as the Queen of Heaven. “Ave Maria, Stella Maris”, hail Mary, star of the sea, is how an old hymn from the 9th century begins, which is still part of the Liturgy of the Hours in the Catholic Church today.

Red is often her dress and symbolizes love and warmth, but also the blood, which refers to the sacrificial death of her son. Green is sometimes the undergarment that peeks out from under her dress and stands for the hope of paradise and eternal life. Sometimes she wears a white dress, a sign of innocence and perfection that hardly needs any explanation.

Mary is rarely mentioned in the Bible; the most frequent mention is made of her by the evangelist Luke, whose account also contains a detailed description of the Christmas story. Interestingly, Luke is regarded in tradition as a doctor and also as the patron saint of painters. Some early church writers recount how confreres asked him to paint a picture of the Virgin; a subject that is mainly found in medieval depictions. Whether Luke used the same precious blue lapis lazuli for the Virgin’s mantle as his later colleagues is not reported. As a true artist, he would certainly have appreciated the intensity of the crushed mineral, which was so expensive that some clients stipulated exactly how much of it could be used before painting.

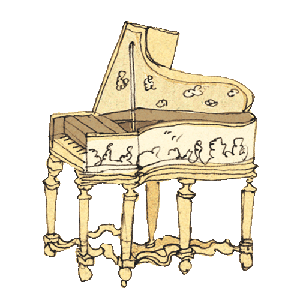

Throughout the centuries, the attributes for depicting Mary have remained the same. In this painting by Karl Begas, which hangs in the Picture Gallery at Charlottenburg Palace, the triad of red, green and blue shines beneath the gentle face of the mother holding her child in a protective gesture – not for nothing one of the most touching motifs in Western art.