24

The Pauline Miracle

The image of the Holy Family on Christmas Eve is one of eight scenes from the life of Mary and her son, carved around 1490 and becoming the most important medieval altar in the trade fair city. Today it is once again prominently displayed in the Paulinum in the center of Leipzig, but for a long time this was not foreseeable. Walter Ulbricht, known for his rigorous hatred of church buildings, triggered the destruction of a historic building not only in Leipzig, but here the demolition of the St. Pauli Church had caused a particular rift in society that refused to heal.

The original building belonged to a Dominican monastery and had been closely linked to the local university since it was founded in 1409. Many professors were buried here and often had very valuable artistic memorial plaques erected to keep their names in the city’s memory. With the Reformation, the monastery was secularized. Elector Moritz, who also created schools in Schulpforta, Grimma and Meissen, transferred the church building to the university and Martin Luther consecrated the church. As elsewhere, altars and other decorations were removed, but the beautiful carved altar was preserved.

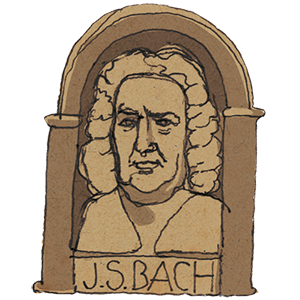

Over the centuries, this church had endured much, but nothing was comparable to the day in May 1968 when the church, which had remained undamaged during the war, was handed over to the demolition squads. Shortly beforehand, important works of art had been saved and just minutes before the demolition, the cantor played one of Bach’s toccatas on the historic organ, which Bach had once sat at, amidst the noise of the drills. Before he was thrown out, he drew a cross over the last note he was able to play. With the construction of the Paulinum 50 years later, the rescued works of art found their place again; a miracle that could not have been expected in 1968.